Bushrangers, larrikins and bashers

Ghosts of Australia's criminal past…

Australia is fun. Beautiful weather, wide-open beaches, forests, friendly cities, fascinating wildlife.

I’ve just returned from a few weeks in Melbourne and Sydney, with a spell near the sea on the Great Ocean Road, and a day spent at the Australian Open.

But for someone with an interest in crime and history, I had to take some time to dredge through the country’s less respectable past. This was a land originally used by Britain, after all, as one big dumping ground for its criminals.

There were 775 convicts on the First Fleet to set sail for Australia in 1787, some for crimes such as stealing a watch. For a time the colony appeared to be on the verge of anarchy and the authorities relied on hangings, quarterings and lashings to keep order.

Sydney’s Justice and Police Museum, housed in the city’s former police station and court, tells the tales of gangsters, killers, forgers, ‘bashers’ (thugs), conmen, bushrangers (highwaymen), larrikins (hooligans) and others who passed through its courtroom and cells.

Homosexual men were also deemed to be public enemies. If caught in the state of Victoria, they would be shamed, flogged and thrown in jail for 10 years.

Wife-beaters not so much. A week or two in the slammer for them.

Ned Kelly’s armour

I also visited the state libraries in Sydney and Melbourne, which were both jaw-droppingly impressive. Huge, beautiful buildings with treasure troves of books, archives, newspaper libraries and genealogy resources – all easily accessible to the public.

The Victoria State Library in Melbourne also has Ned Kelly’s armour on display in a reading room, worn when he was shot and caught by police at the Glenrowan siege in 1880. The rest of the infamous bushranger’s outlaw gang were killed in the confrontation.

I picked up a book called Hanging Ned Kelly, by Michael Adams. It catalogues the parade of convicts pressed into being hangmen during Sydney and Melbourne’s formative years, a job no respectable person wanted.

The executioners were often drunk, if not during the hangings, then nearly always afterwards, when they would be arrested on a bender in town and fined for their execution fees.

Something of a Robin Hood legend took hold around Ned Kelly, whose gang stole, killed cops and evaded police for years. Some hostages said the gang were handsome and courteous, and Kelly portrayed himself as a victim of police persecution who was fighting back.

Anyway, the man who got the job of hanging Ned was, as Adams’ book coins it, a ‘shit-shoveller-turned-quack-doctor-turned-drunken-chicken-thief’ by the name of Elijah Upjohn.

Criminal hanged by a criminal

Born in Shaftesbury, Dorset, in 1822, Upjohn was transported to the colony for burglary and stealing shoes.

Some 34,000 people signed a petition for Kelly to be reprieved after he was found guilty of murder, it being felt he had been persecuted and acted in self-defence.

There was no reprieve. On 11 November 1880, Kelly encountered Upjohn on the scaffold.

The Melbourne Herald reported Kelly’s last words as, ‘Such is life.’ Several reporters in attendance said Kelly had died instantly. If true, he was lucky as Upjohn was a hangman with no training or experience and could have easily bungled the execution. He was paid £5.

The following year he was spotted in the street, stoned by onlookers and kicked, his dispatch of Kelly not forgotten or forgiven. He ended up as a vagrant. Having fled to Sydney, he was found dead in a tent, rumoured to have been poisoned. Such was his life.

Just before Christmas I read Albert Pierrepoint’s 1974 autobiography about his career as Britain’s hangman, which I wrote about earlier. I feel now that I know as much as I ever want to about the cruelty, moral cowardice and injustice of capital punishment.

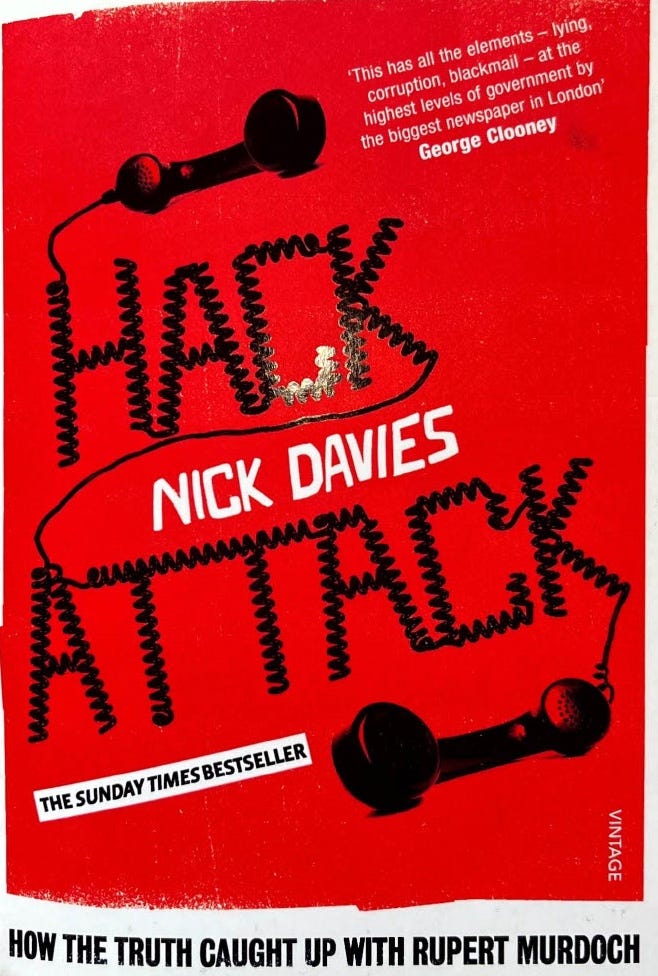

While in Oz, I finished reading Hack Attack: How the Truth Caught Up with Rupert Murdoch, by Nick Davies. It had been on my to-read pile for years and for some reason I suddenly felt it would be a good holiday read. It is one of the very best books I have read by a journalist – detailed and absolutely engrossing. Davies, a Guardian investigative reporter, played a leading role in exposing Fleet Street’s horrendous hacking practices. This took courage, doggedness and skill. With the Murdoch press, the Telegraph and the Mail group – not to mention Scotland Yard – all doing their damnedest to conceal the truth about the spying on law-abiding people, the hacking, blagging and corruption, Davies and his editor, Alan Rusbridger, had some heavyweight attacks to fend off. The book offers precious insights into much of what is wrong with modern Britain and the baleful climate promoted by a billionaire-owned media. The country needs the investigative verve and determination of reporters like Davies more than ever. Sadly, he’s now retired, but, for anyone who’s interested, you can enjoy some of his brilliant reporting here.

Here’s a link to the interview I did with author/radio host Ron Chepesiuk on Crime Beat, an informative and entertaining true-crime show in the US. The main subject was my book, The Real Ted Hastings, and the adjacent subjects of corruption and the TV drama Line of Duty, but also writing and researching crime cases.

A Cruel Love: The Ruth Ellis Story is a drama coming to ITV soon. Based on an acclaimed biography by Carol Ann Lee, A Fine Day for Hanging, it will star Lucy Boynton as Ellis, the last woman hanged in Britain. The case shook public opinion and focused critical attention on the death penalty as never before. The setting is mid-1950s London. Ellis was a young nightclub hostess who became involved in an abusive relationship with racing driver David Blakely, whom she ended up shooting outside a pub in Hampstead. She admitted her intention to kill, but questions of domestic violence, coercive control and the role of her other lover in the crime (he gave her the gun) were glossed over the trial. The case has been depicted many times in TV dramas, films – notably 1985’s Dance with a Stranger – on stage and radio. It will be interesting to see what this latest series will say about it.

Seems like the profession of executioner has nearly always attracted the most desperate and dissolute men around (have there been any/many women executioners?).

Fascinating trip and info on Ned Kelly's hangman. Another interesting character was Canada's 1920's hangman, Arthur Ellis (real name Arthur English - he took the name Ellis after UK's hangman John Ellis). UK born English answered a job advert for a hangman for Canada but by the time he came to execute US serial killer Earle Nelson (for the murder of my own ancestor, Emily Patterson, by the way), he was well past his game and was an alcoholic. Unfortunately, he bungled a few executions, subjecting two felons to decapitation and another couple to slow strangulation. I enjoyed researching this strange character for my own book about Nelson's forgotten victims - 'The Forgotten Forty-Four'. English went the way of several other hangmen, deserted by his wife, alone and in poor physical and mental health.