Hammersmith Nudes Killer – did detectives eventually unmask his identity but cover it up?

This case from the 1960s has been covered in documentaries, books, podcasts and on YouTube. But now there is a new and bewildering development…

Did certain Scotland Yard detectives discover the identity of the 1960s’ Hammersmith Nudes Killer and keep it a secret?

That’s the mind-boggling question I’ve been asking myself after chatting with a forensics officer of the time who contacted me this week.

Having written a book on the series of six murders and the ensuing failed investigation, I received a message from a man called Anthony Phillips, who worked on the case while at the Metropolitan Police Forensic Science Laboratory.

Mr Phillips, who is now 83, discovered the most vital piece of forensic evidence that detectives had during the enormous manhunt – the particles of paint found on the bodies of four of the women who were asphyxiated and left in the open.

His extraordinary account centres on evidence brought to him in 1969, four years after the final murder. He was asked to test samples found in a car boot, which he did.

‘Whoever that car belonged to, he was the murderer,’ Mr Phillips told me.

However, no arrest was made, no announcement followed.

If Mr Phillips’ account is true, it raises huge questions.

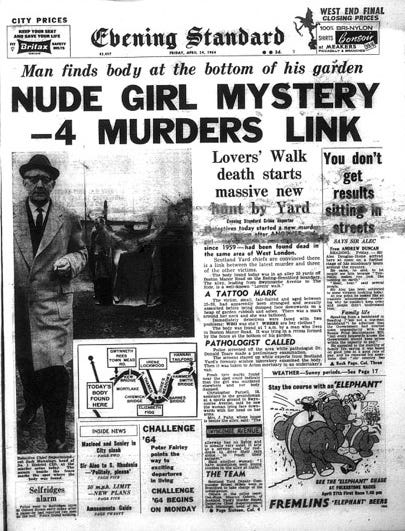

Hundreds of officers hunt the west London serial killer

Swinging London woke on the morning of 24 April 1964 to the fact that a depraved serial killer was at large.

The body of a woman, Helen Barthelemy, aged 24, had been found in an alley in Brentford. She was the second discovered that month, and the third since February. No one could be in any doubt now that one man was stalking London’s streets on a killing spree.

Helen, like the other victims, Hannah Tailford and Irene Lockwood, was a sex worker. They touted for business from kerb crawlers on the streets of west London – Queensway, Portobello Road, Shepherd’s Bush.

Each victim had all of their clothing removed, along with their jewellery – even their false teeth. The women were all petite, around 5ft 1in, and had come to London and ended up working on the streets to make ends meet.

All were left out in the open – Hannah on the Thames foreshore, Irene in the Thames by Chiswick. They would be followed by Mary Fleming, found in the street in Chiswick, and Frances Brown, left in a Kensington car park.

Finally, in February 1965, Bridie O’Hara was spotted down the side of a building on the Heron Trading Estate in Acton.

Scotland Yard’s biggest ever manhunt

When Bridie was found, the victim count was at six, and Scotland pulled in one of its top five investigators, Det Ch Supt John du Rose. He was called ‘Four Day Johnny’ by the newspapers because of the speed with which he closed his cases.

The resources given to du Rose to find the killer would dwarf the scale of modern investigations. He had a 200-strong CID force, plus another 100 officers. The Special Patrol Group of 300 was also put at his disposal.

The licence-plate numbers of hundreds of cars was taken down by officers on all-night duty at various points around west London, huge numbers of drivers and others were interviewed, while female officers dressed as prostitutes were stationed on pavements to gather intel on suspicious punters.

Despite the efforts of this army of officers, detectives had virtually no solid forensic evidence to go on. By taking the women’s belongings, the killer was leaving scant forensic evidence behind.

That was until Anthony Phillips made a dramatic contribution. He had joined Scotland Yard forensic science team in 1963, where he was allocated to the chemistry lab.

‘I used to do the analysis of alcohol samples for drink driving,’ Mr Phillips told me. ‘I specialised in tool marks, paint samples. We did a fair bit of toxicology.

‘One day, we heard that one of the sergeants had been to a postmortem where a lady had been found naked on some land at Kew. They said they’d seen some, what they called, dirt on the back of the body. And my boss said, “Tony, would you like to have a look at that and see what you might find?”’

What he found was paint globules on the body – red, black, white and turquoise, probably spray paint.

‘Then the next body came in [probably Irene Lockwood], and I looked at it and said, bingo, red, black, white and turquoise spray paint samples.’

He told his bosses he considered the bodies to be linked. The third body, Barthelemy, had the same paint specks.

Mr Phillips then examined the areas where the women had been found and discovered there was no material at these that tallied with the paint samples.

This was a big forensic breakthrough for Scotland Yard. Mr Phillips had demonstrated that the victims had been kept at a location where they had come into contact with the paint globules before being left at the deposition sites.

If detectives could find that site, or the car in which the bodies were transported that may well have had the paint samples in it, they would be much closer to knowing the killer’s identity.

When final victim Bridie O’Hara was found on the Heron Trading Estate, Mr Phillips confirmed that she too had the paint samples on her.

‘John du Rose has been appointed and he came up to see me,’ Mr Phillips said. ‘I said, would you like to have a look down the microscope to have a look and see what we're talking about? He said, Oh, my eyes aren’t very good, I’ll leave it to you.’

Crucially, Mr Phillips went back to the trading estate, took samples from the area and located the derelict building where the latter four bodies picked up the paint globules (the first two were found in the Thames and no samples were found on them).

Frustratingly, the unused location did not lead police to the killer. They could tie no one suspicious to the address, or find anyone seen using it.

Mr Phillips says he suggested to du Rose that officers monitor cars at the industrial estate and take samples from them, in the hope of exposing the killer. Du Rose agreed and Mr Phillips got additional help in the lab to deal with the samples coming in.

‘At the same time, we were using Zeiss microscopes up to a hundred times magnification,’ he told me. ‘Zeiss were consulted about what we were doing, and they loaned us three 250-timed magnification microscopes, which were the cutting edge of microscope technology in those days.’

Despite this mammoth effort, the killer evaded all attempts to catch him. ‘We did it for something like nine months to a year of looking at all these samples, but there was absolutely nothing to connect anybody with those colour schemes.’

The killings stopped after Bridie O’Hara, and the investigation was quickly wound down. Because the victims were sex workers there was little sympathy for them and no outcry to pursue the murderer once the killings ceased.

Was a there a cover-up?

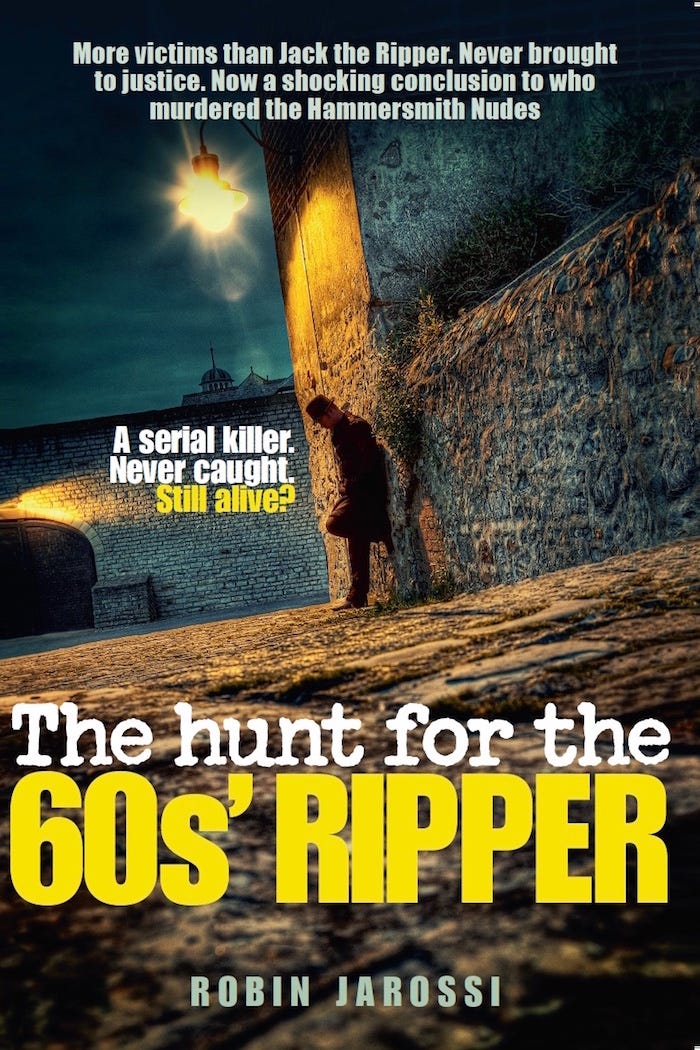

Mr Phillips contacted me because I wrote a book about the case, The Hunt for the 60s’ Ripper (Mirror Books 2017), and he had never told anyone about the events that came next.

Around three years later, he had left the lab and become on of the Met’s original scene-of-crime officers. He was trained as a detective and given experience in the fingerprint branch, to boost his expertise in the lab.

He recounts what happened around this time: ‘I suddenly got someone buttonhole me and said, Oh, Tony, what are you doing? We’ve got something that might be of interest to you. Would you like to have a look at this sample? I said, It’s nothing to do with me any longer. He said, Listen, stop being bloody awkward, I’m asking you, would you look at this sample?

‘He said, It’s some tapings that we’ve taken from a car [meaning, adhesive tape used to lift fibres, hair, specks and other evidence from a scene].

‘So I went and borrowed a microscope, sat down, and lo and behold, the colours matched. I said, where did that come from?’

The detective who had approached Mr Phillips said, rather oddly, that he did not know where the sample had come from.

‘He says, I don’t know, but it’s come from a car. There’s no registration number on the packaging, nothing at all. It’s blank.’

Mr Phillips told the detective he needed to know and would the officer find out for him.

‘He phoned up the officers that had produced it, and they said they couldn’t tell him either. It never ever came out where that sample [came from], whatever happened.

‘The owner [of the car from which the taping came] was the perpetrator of the nude murders.’

I told Mr Phillips I was stunned by his account. He replied, ‘Well, no one’s ever asked me about it like you are. So you are hearing it first. The family know, but nobody else really knows.’

One explanation that he considered was that the car’s owner was dead at this time, which Mr Phillips puts at being 1969, ‘May, or thereabouts’.

However, he soon discounted that theory. ‘Because I would’ve thought they would’ve had to go to the coroner, and [say to] him, Look, these are the jobs [murders] that we had years ago. We got some samples. They come from a car and that person is deceased. In which case, the coroner would say, okay, fine, written off. We can’t do anything about it. But I’ll mark it up that he was the murderer.’

But nothing like that ever happened.

Ex-police officer, or ‘someone in high society’

I found Mr Phillips to be knowledgeable and compelling when discussing the case with him. He talked about his eventful career, how he went on to teach at the University of West London after retiring in 2000, and some of the cases he was involved in.

If we assume he is telling the truth, that he is not in some way mistaken, then what on earth is the significance of the sample he was asked to test in 1969?

He was not told how the sample had been discovered, or what the make of the car was – ‘I couldn’t find out. Nobody would tell me. I couldn’t understand why it was so secret.’

Mr Phillips has asked himself if the sample could have come from the car of an ex-police officer, or ‘someone in high society’.

‘But none of it will be provable until you actually found out the reasons why,’ he said.

He is adamant, however, that if that sample did come from a car detectives had found some time after 1965, that was case closed.

‘The owner of that car was the murderer.’