Internet killed the magazine staff

Introducing Persons Unknown – crimes, victims, investigations

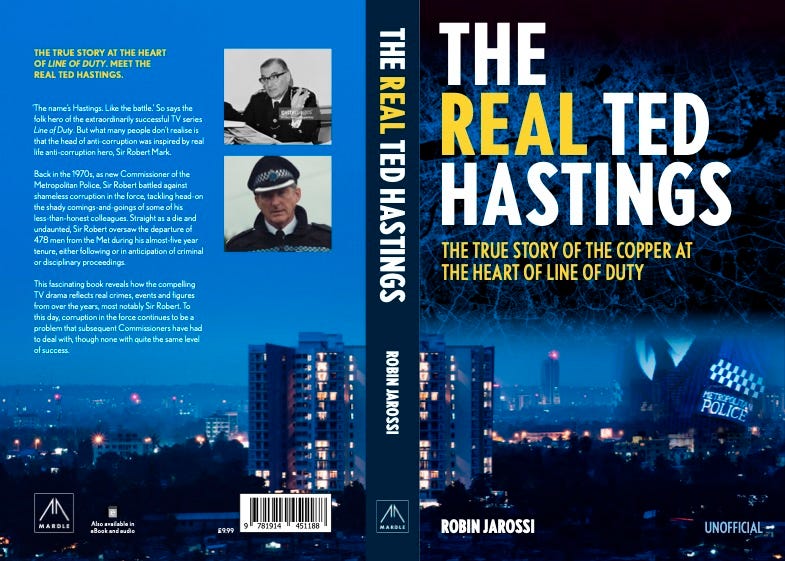

Front and back cover of The Real Ted Hastings, Mardle Books

From the ashes of a magazine…

My metamorphosis from ink and paper journalist to Substacker covering true crime has taken seven years. It began in 2016, though I didn’t realise this at the time.

I was working on Special Projects in the Daily Mirror offices at Canary Wharf, London. For a year we had been gathering content for a new true-crime magazine.

My role was effectively features editor – commissioning articles, writing and forming ideas for content. An enjoyable challenge.

At the very moment the title had been written, proofed and was ready to go to press – after 12 months of diligent work – the project was cancelled.

True-crime magazine bumped off.

Who killed it?

The Mirror’s owners, Reach PLC. All down to cold feet. The magazine fell victim to jitters about the risks of launching new publications in the hostile age of online news and social media.

Frustrating, but it was hard to argue with their reasoning.

However, a new door opened. It was suggested that a feature I had worked on for the stillborn magazine could be developed into a book.

The subject was a series of unsolved murders in west London in the early 1960s. Even though I had grown up and live in the city, I, like many Londoners, had never heard of this case.

In 2017 The Hunt for the 60s’ Ripper was published by Mirror Books. I wrote a feature about the case for The Daily Mirror and the BBC made a documentary about it, Dark Son, on which I was interviewed.

This led to my appearing on a range of crime documentaries on CBS Reality and further books. Last year Murder by the Sea was published, covering 10 cases featured on the CBS Reality docu-series of the same name (co-authored with the programme’s director, David Howard).

And this month, Mardle Books followed that up with The Real Ted Hastings. This time the subject shifted from homicide to corruption, and how the hit BBC drama Line of Duty reflects the real world of bent coppering and failing justice.

The motive behind Persons Unknown

I have met quite a few fascinating experts and academics. And not all the material gathered or stories I hear make it to the page.

Person Unknown, coming out on Thursdays, is a space in which I would like to share perplexing questions and fascinating angles on old cases.

True crime is having a moment, fired by an explosion of TV channels, podcasts and books exploring the subject. While the more exploitative manifestations of murder voyeurism rightly draw criticism, there are many serious writers and producers offering outstanding research and portrayals of crime and what it says about our lives.

Persons Unknown will share the curiosity most of us have about how crimes occur and how investigations work – or don’t work. There will be threads and polls. Feedback, of course, is welcomed.

The title has connotations in UK law, referring to an interim injunction taken out against ‘persons unknown’, such as protesters or trespassers. It can suggest unidentified victims or suspects.

Look at a crowd of persons unknown. How many might commit a crime? Is every one of them capable of murder in the right circumstances?

The title also conjures up questions when the identities of those concerned are known. Who was this perpetrator really? And how did a victim have the misfortune to be in their attacker’s orbit? What made this man a killer, but not that man?

There are further puzzles. How could persons unknown on the jury come to that verdict? And getting to know persons previously unknown from 50 or 100 years ago offers revealing insights to how our attitudes have changed, or perhaps haven’t changed enough.

Cases to be reopened

Because my new book is about corruption, I’m going to kick off with that subject next Thursday. London’s Metropolitan Police are in crisis. I’d like to compare how the force’s situation today compares to the corruption crises faced by Commissioner Robert Mark in the early 1970s. Is Scotland Yard in a worse state in 2023?

The Blackpool Poisoner case of 1953 is one of the most bizarre and unsettling I’ve come across. Was Louisa Merrifield the victim of a miscarriage of justice when she was hanged for poisoning the woman she was caring for? If she was guilty, why did her husband, who stood to gain as much from the victim’s death as Louisa, escape the death penalty?

I’ll share an extraordinary piece of deception apparently executed by a bent 1970s detective that is so outrageous even the writers of Line of Duty would shy away from including it in the drama.

Following the Stephen Port case in the UK, it’s interesting to ask why it is that police in the UK and USA often fail to spot a pattern that means a serial killer is at large. And why are serial killers often attracted to joining the police?

Unsolved cases, miscarriages of justice, victims undeservedly forgotten.

As they used to say at the start of that old TV crime drama, there are eight million stories in the naked city.

How could we not interested in that?