Why did Scotland Yard's biggest manhunt fail: Part 3

Dictatorial senior officers, information overload and bad luck defeated London's finest in the hunt for one of the capital's worst serial killers

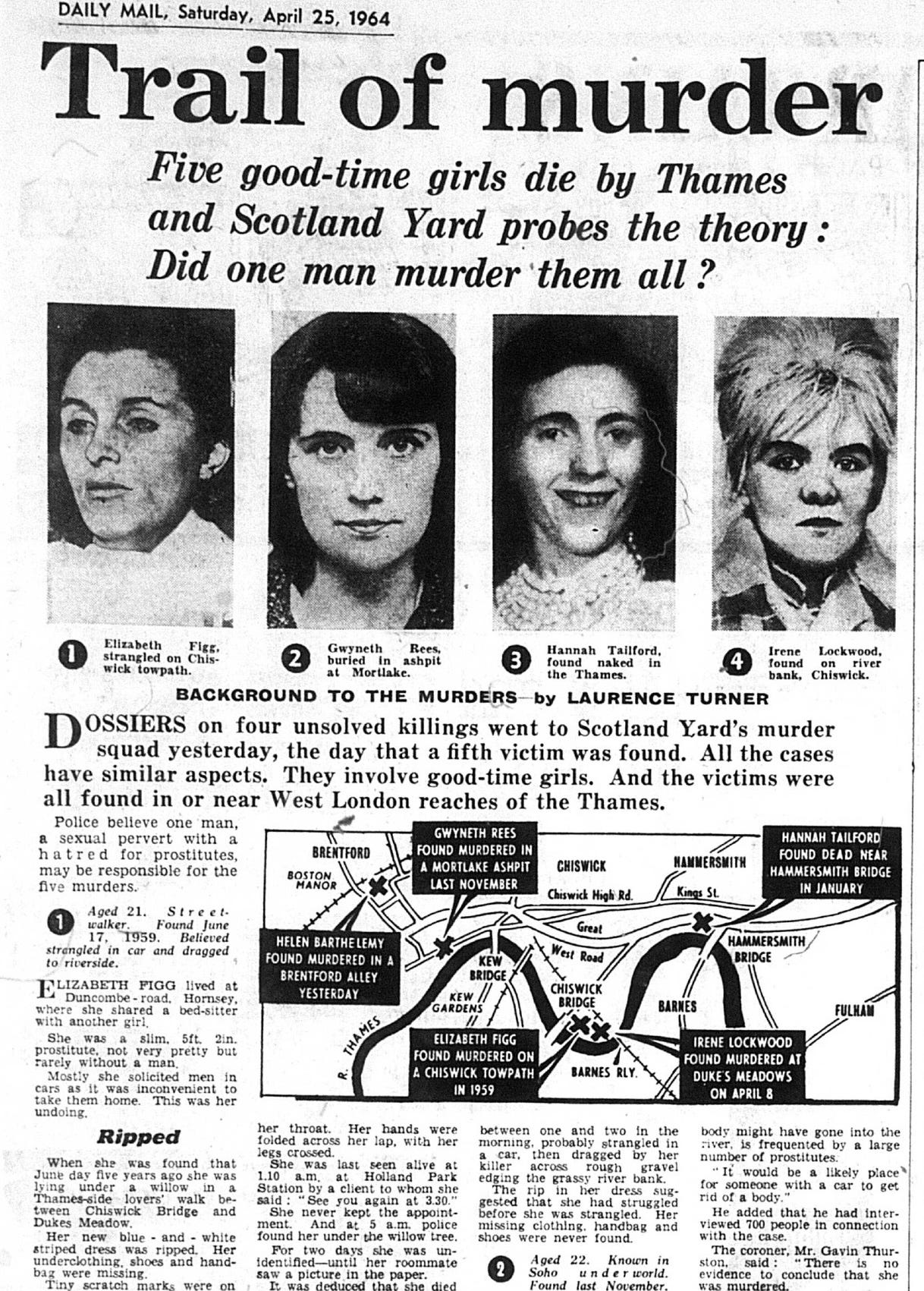

Somebody killed six women in swinging 1960s London and got away with it. He was probably spotted a couple of times, but each time he melted back into the capital’s anonymous corners.

It is a crime that taunts us from the past. To this day there has been no justice for the victims – Elizabeth Figg, Hannah Tailford, Irene Lockwood, Helen Barthelemy, Mary Fleming, Frances Brown and Bridie O’Hara. While all media attention at the time was devoted to the police investigation and the lurid lifestyles of London’s ‘good-time girls’, the women themselves were largely forgotten.

Time and again, suspects were not picked out in an identity parade, their premises were searched and nothing was found, forensic samples were taken but no match was established. Time and again, a senior detective noted there was ‘no evidence to hand despite many inquiries’, the suspect ‘did not possess a car, nor could he drive one’, ‘no evidence was found’, ‘again no useful information was obtained’, ‘no evidence was found to connect him to any of the murdered women’. And so on.

There are two possibilities here. The first is that the murder squad had identified their man but failed to realise it. Leading detective Bill Baldock mentioned on several occasions that ‘time or lack staff’ did not allow certain inquiries to be completed. Just as detectives on the Yorkshire Ripper hunt confronted Peter Sutcliffe nine times and let him go, did one of these curtailed inquiries enable the Nude Killer to slip away?

The second possibility is that the guilty man was never even suspected by detectives. Geographic profiler Kim Rossmo told me, ‘It is possible that the reason they were unable to find sufficient evidence to charge anyone was because they never had the right person... There is nothing about the identified suspects that suggests they should be regarded as anything other than suspects. Dozens, if not hundreds, of people with dodgy pasts and suspicious behaviours come to the attention of the police in major inquiries, especially in serial murder cases. Concluding that a suspect is the offender in the absence of very strong evidence is a mistake.’

The most promising suspects were the men who received the most in-depth police scrutiny, including the Disgraced Cop and night watchman Mungo Ireland, mentioned in Part 2 of this post. It is easy to assume that the killer was among the group of top suspects. But hundreds, possibly thousands, of other men were also questioned or checked out.

As Rossmo makes clear with this statistical example – ‘If you look at it in just numbers, and I’m looking at 7,000 suspects they interviewed [on the Heron Trading Estate], the probability that he is in the 6,990 who are not top suspects is still higher than the top 10. Just bear in mind that even if you have the top suspects, it could be one of the ones that just didn’t come to their [the murder squad’s] attention.’

Looked at in these terms and in the light of problems already laid out – a vast investigation spread thinly that could not properly process all the data coming in – it is perhaps not that surprising that a devious, determined murderer could stay in the shadows. One fact should be borne in mind: the officers on this case had never experienced an inquiry of this type or scale before. What had worked on previous cases did not work here. This had been a huge challenge for everyone involved.

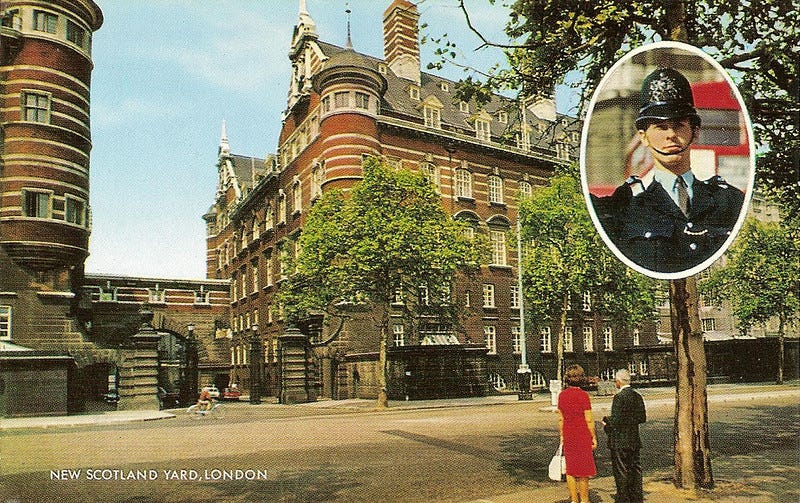

The Nude Murders hunt was certainly not the first or last to struggle to catch a serial killer. Jack the Ripper had infamously escaped Scotland Yard’s detectives just 77 years earlier. The Zodiac Killer in the US taunted the authorities in letters to the San Francisco Bay Area press, but he was never caught and the case, dating from the late 1960s, remains open today.

And the nature of the apprehension of some serial killers further attests to how difficult they can be to identify, even showing that luck can be a vital ingredient. Ted Bundy confessed to 30 murders in seven US states between 1974 and 1978, though the actual total could have been higher. It was not a brilliant piece of Sherlockian sleuthing that unmasked him but a routine traffic stop by a Utah Highway Patrol officer, Sergeant Bob Hayward. He simply became suspicious of Bundy’s VW Beetle passing at 2.30am through the pleasant neighbourhood where Hayward happened to live. It was another diligent patrol officer, Sergeant Robert Ring, accompanied by probationer Robert Hydes, who brought Peter Sutcliffe in for questioning after a routine stop in Sheffield on 2 January 1981. A five-year reign of murder that shocked Britain was brought to an end by uniformed officers on patrol. Thank goodness for no-nonsense sergeants.

If there was any luck going round, the Nude Killer had it all. But were there weaknesses in the Nude Murders investigation? By looking at the case through modern eyes it is possible to see how contemporary police practice has made improvements out of past failures, and to get some insight into how the killer cheated the massive hunt to find him.

How would Scotland Yard hunt for the Nudes Killer today?

Driving through west London with two retired detectives in May 2016, I found it almost bewildering to see how the area still closely resembled the 1960s city terrorised by the Nude Killer, while at the same time having changed so dramatically.

We were visiting the body-deposition sites, as would be done in a cold-case review. This was at the suggestion of Brian Hook, who spent the majority of his police career serving on specialist investigation units and was a crime-scene examiner. We were on a sobering tour to get into the mindset of the murderer and consider the original investigation from a modern perspective.

Brian and his colleague Andy Rose, a former Met detective inspector, are both now lecturers in forensics, investigative skills and criminology at the University of West London. They share an ironic sense of humour that police officers seem to specialise in and between them have a wealth of experience in dealing with serious crimes.

‘There’s no doubt society had a different view in the sixties,’ said Andy. ‘From my experience of investigating sexual offences against prostitutes even into the 1980s it was seen as a case of, “Why would you [bother to] do that?” The women are putting themselves out there. Whereas obviously they are just as much victims as anyone else, probably suffering more than many.’

Brian’s first impression was of how close the crime scenes were. ‘All the deposition sites are within two or three minutes’ driving.’

The tour of the deposition sites brings one fact home with force – just how anonymous the killer was driving around west London with a corpse in his car back then. Not much traffic (1965’s 12 million licensed vehicles compares to 2011’s 34 million), few police patrol cars, and little incentive for the police to stop cars when they had no on-the-spot means of verifying vehicle ownership. ‘You think about him marauding around and getting stopped by the police, but it was unlikely,’ Brian said.

‘There was no national computer to check for stolen vehicles, so why would a police officer begin stopping people? There were not many police cars. You would have one area car for the whole district. Today you would have area-response cars, but these were the days before Panda cars [introduced in the mid-60s]. Back then, people walked, simple as that.’

However, the dangerous moment for the killer was getting the body out of the vehicle, as two deposition sites made clear. The alley off residential Swyncombe Avenue was the first occasion on which the murderer almost gave himself away. It was around 6am when he reversed a short distance into the 200-yard track linking Swyncombe Avenue and The Ride on 24 April 1964. It would have been daylight as he lifted the naked body of Helen Barthelemy and dropped her by a fence.

Then he tore off, swinging into Boston Manor Road and almost colliding with motorist Alfred Harrow, who had to brake violently to avoid a vehicle he described as a Hillman Husky or Hillman Estate.

‘He took a huge risk here,’ Brian said. Then he recalled the press photographs of detectives standing all over the crime scene. ‘The forensic capabilities now are far, far more advanced. To have a body found in these circumstances and then three hours later to have a post-mortem, you’re like, Oh, hang on.’ By which he meant the forensic examination at the scene would have lasted many more hours today. ‘And the cop standing there on potential tyre tracks peering over the screen [that had been erected to shield the victim]. It’s not a question of blame, it’s just a lack of knowledge and training. So those actions would be different today.’

The killer described in the police report as ‘cool and calculating’ was certainly not so in July that year. The two detectives were, like their 1960s forebears, struck by how close the Berrymede Road disposal of Mary Fleming was to where the decorators spotted the van driver acting strangely behind the ABC restaurant on Chiswick High Road. ‘This is a weird spot,’ Brian said. ‘It reeks of desperation.’

Both former detectives concurred that the killer was very likely to have been a local person. The area where the prostitutes were picked up were the obvious kerb-crawling streets, such as Bayswater and Queensway. But the deposition sites – down by the river, an alley, the side of a storage shed – these reveal his local knowledge.

Twenty-first-century Notting Hill, an area of spectacular wealth north of Kensington, is a stunning contrast to the boarded-up houses, piles of trash and peeling plaster work that was the norm there half a century ago. Mary Fleming once slummed it in a multi-occupancy flat with several families sharing facilities on Lancaster Road – that same property costs more than £3.5million today. The kerb-crawlers and street workers have vanished from Queensway and Bayswater, the trade having migrated to the internet.

The Heron Trading Estate, scene of the last deposition, has also changed considerably. The spot where Bridie O’Hara was left between the warehouse and the railway siding has gone, as new industrial units have replaced many former businesses.

The final murder – why did he stop?

This was the final Nude Killing. Because the murderer had effectively drawn attention to his body-storage site by leaving Bridie outside the building where he had been keeping his victims, it was tempting to view this as a sign-off by him. So was that a final flourish to taunt the police? I’m done and this is where I’ve been keeping them...

Brian did not think so. ‘I don’t think it was a decision consciously made not to do it anymore. There’s been an event [that diminished his need to kill]. The body was in an area where nobody goes – behind the shed by the railway line, partly covered up. It could have been there for months and months if somebody hadn’t made effectively a chance finding.’

So, why did he stop?

Andy said, ‘He might have been arrested, might have died. Everyone’s an individual.’ He cites the example of Ipswich serial killer Steve Wright, who only turned to killing them at the age of 48.

Leaving aside technological advances that were simply not available to the 1960s murder squad – DNA, modern forensics, CCTV, tracking of mobile phones and the like – there were problems with the way the 1960s team was set up in the face of what was a complex and data-heavy investigation.

Looking at how today’s murder inquiries work – which have been built on and corrected past investigative failures – it becomes clear where Detective Chief Superintendent John du Rose’s squad got bogged down. Two major inefficiencies become obvious.

First, the Nude Killer investigation was too unfocused, and, second, the squad’s dictatorial hierarchy – standard for the time – could not cope with the huge amount of statements and data generated by six major, concurrent murder probes during 1964–65.

Crime fiction fans will have heard about the importance of taking control of an investigation in that first ‘golden hour’, when clues and memories are freshest. In the 1960s a lot of early decisions were taken by constables who were first on the spot and awaiting the arrival of their inspector. ‘In those days there wasn’t a permanent murder team,’ Brian said. ‘Whoever got called down to the crime scene was whoever was on duty. Never mind if the on-call detective inspector was good at murder investigations or not.’

Andy adds, ‘A murder would happen and two or three detectives would just get taken out of the office – right, you’re on this murder now. The likelihood was you chose people who didn’t have a lot on. You were reliant on them being paired up with somebody who knew what they were doing.’

Today’s priority is to get a specialist expert team there as fast as possible. A car carrying the Homicide Assessment Team would aim to be at the crime scene within 10 to 30 minutes. Their job is not to go onto the scene but, if required, to call in a specialist homicide unit, alert a senior investigating officer and get efforts such as house-to-house inquiries under way.

Forensics are obviously more advanced today. The scene assessment of the body in situ would probably last for many hours more than it did in the mid-sixties, more samples – soil, vegetation, tyre tracks – would be taken, and the victim may even be examined on the spot, with temperatures taken for potential time of death.

The point is to gather as much information in the golden hour or first few hours. The second phase of the investigation is to gather the team together. ‘You’ve got your SIO [senior investigating officer] and you’re going to have your office meeting,’ Andy said. ‘These are very open and while they are led and directed, everyone’s view is listened to equally. It’s not hierarchical.’

This open approach was not the norm in the 1960s. It recalls the comment of former detective superintendent Chris Burke: ‘Other members of the enquiry were “mushrooms”, kept in the dark and only told what the detective superintendent or inspector wanted them to know.’

Nepotism, a dictatorial boss and data overload

Brian expands on this. ‘There was nepotism. You had a system of bag carriers. You would have a detective superintendent and a detective sergeant, and the sergeant would be the superintendent’s bag carrier, basically a PA. It was very much a closed team at the top.’

It is a point that had been made to me by several former detectives. The attitude was that the top detective was the clever, experienced one. This may have worked on smaller, less complicated investigations, but when faced with the tidal wave of tips, statements, car sightings, house-to-house inquiries, dust samples and the rest, there is no knowing what connections or possibilities were missed.

Consider the ‘immensity of the operation’, as Bill Baldock referred to it, of interviewing more than 7,000 current and past employees on the Heron Trading Estate, where the bodies were stored. As Brian explained, ‘The SIO has to read every single statement that is relevant. Now, even if 10 per cent of those 7,000 statements are relevant, that’s 700 statements. There is no way John du Rose could ever have read those and assimilated where they fit in at all.’ And there were tens of thousands of further statements on top of that for du Rose, Baldock and the ‘closed team’ under them to get through.

Brian adds, ‘TV programmes still go back to that – Oh, it’s this person that solves it. That’s because what happens now in reality wouldn’t make good TV.’

‘I think that is the biggest difference,’ Andy added. ‘Nowadays, you can’t have a dictatorial SIO. The system doesn’t allow it, the review processes don’t allow it. Within 21 days of a crime, somebody’s already started to review those first 21 days – what have you done, how did you do that?’

The culture now is of having outside detectives quickly moving in to review the decision-making on an investigation.

Senior investigators are scrutinised more closely and have to fill out decision logs detailing what they did and did not do, why and at what times.

‘Which would never have happened in the 1960s,’ Andy said with a laugh. ‘They wouldn’t have countenanced anybody else coming in to somebody at that [du Rose’s] level and saying, “I want to have a look at the way you’re running this investigation...” Initiative was not encouraged. A senior officer’s justification used to be we’re doing it this way because I say so. That’s not the case anymore.’

However skilled were John du Rose and his inner sanctum, it is clear they were swamped by the investigation.

A huge wall of administrative shite

‘You can see what they were doing but it was so unproductive,’ Brian said. ‘Trying to find out the registered keepers of all those cars – all that actually did was take a huge amount of time and resources. It was so unproductive, it wasn’t focused. It was a case of, “Let’s cast the net out and see what we drag in”, which is just nonsensical and counterproductive.’

We also know about the daunting hours and overtime that went into these efforts. But again, often all that was achieved by the long hours put in by senior and junior officers was to generate a mass of useless information. Think of the effort devoted to the night observation of vehicles, for example, sitting in vans for 12 hours at a time, peeing into a bottle, taking down numbers. ‘Hard to maintain focus and motivation,’ Brian said. ‘But it was all they had. The problem they had was that it creates such a huge amount of work.

‘You had fixed observation points all round Kensington, Chiswick and Shepherd’s Bush. If they’re told they are looking for a Humber van, they would take the number of every single Humber van. What that means is that in the morning, when they give their lists in, they had to cross-check the lists for vans that appear more than once, and then phone up the councils or take the lists to the councils, who had to physically search for them. Out of, say, 50, 10 won’t be registered to anyone now... And that’s every single night.

‘What you’re doing is creating a huge wall of administrative shite, basically.”

The two former investigators were in no doubt that this kind of hugely labour-intensive investigation could have been scaled down and managed far more effectively today. Investigation is all about elimination, and they point out that a modern inquiry would be able to eliminate far more vehicles and suspects to allow the murder team to focus on fewer targets.

Even without all of the 21st-century technology, however, Brian and Andy are adamant that today’s more collaborative approach to investigation, with its decision-logging and constant assessment, would have greatly enhanced the investigation back then.

Brian said, ‘And because there was no Murder Investigation Manual [a thick book outlining procedures and methods], there was no structure to it. Now there are far more studies into how murders are solved. The SIOs who solve the most crimes are the innovative ones, who’ll say, “This has never been done before but I’ll try this.”’

‘It was very blinkered and prescriptive,’ Andy added.

The corollary is clear: such open-mindedness was far less common in the 1960s.

Perhaps the greatest failure of the old autocratic management style came in the area of information sharing. The drivers of 1,700 vehicles were questioned and dust samples taken, 783 Hillman Husky owners traced, 120,000 residents and business owners seen during the house-to-house operation, and thousands of statements taken. All of these separate bits of information were gathered by individual officers. It would have been impossible for John du Rose and his select senior group to collate and make sense of all that.

Today murder teams have two advantages. One is technological. There are suites of inputters who feed HOLMES 2, the database used by the police since 1994, with statements, forensics, descriptions of witnesses, vehicles, phone numbers, addresses, even details of tattoos. The miracle of the system is that the police can use it to cross-reference data to reveal unsuspected connections – who has phoned whom, witnesses who frequent the same pub – all of which can expose suspicious discrepancies in witness statements.

The other advantage is in the more open organisation of modern investigations, as cited above, with team meetings to share information where suggestions would be listened to. Had that been standard practice in 1965, who knows what unforeseen evidential links might have turned up?

With the data the police today have access to, it is also possible to sift car owners by make, year, colour, locality of vehicle – an undreamed-of advantage in Bill Baldock’s day.

Modern investigative processes are there because of mistakes of the past. The Nude Murder team threw everything they had at finding the killer; they were not the first or last to have difficulties in understanding and trapping a serial killer.

Mistakes had been made in the much quoted case of John Christie. The Rillington Place murderer killed his first victim, Ruth Fuerst, in 1943, but was not exposed, tried and executed until 1953.

In the 1970s, the police would struggle to stop Peter Sutcliffe, the so-called Yorkshire Ripper, during an investigation that was badly bungled. Detectives here ran into similar problems to those that Scotland Yard had in 1964–65 – a stifling command structure and serious information overload that swamped the police and obscured possible leads. Even today, with all the latest technology and knowhow, things still go wrong in serial killer cases.

When I asked Andy and Brian who they thought had committed the Nudes Murder, the police officer’s trademark bleak sense of humour emerged. ‘It was either a friend, a relative or someone they didn’t know,’ Andy said.

Why did Scotland Yard's biggest manhunt fail: Part 1

Why did Scotland Yard's biggest manhunt fail: Part 2

My book on the case, The Hunt for the 60s’ Ripper, can be found here

Photo licence: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/