Hammersmith Nudes Killer cover-up – one theory

A top detective insisted he knew who the serial killer was – but was this part of an effort to deflect from the owner of the vehicle said to contain incriminating evidence?

All sorts of questions were ignited by the news I heard earlier this month, as recounted in my previous post: Hammersmith Nudes Killer – did detectives eventually unmask his identity but cover it up?

To recap – I was contacted by a man via my blog, jarossi.com, who said he had worked in the Met’s forensic science lab in the early 1960s and had dealt with the Hammersmith Nude Murders case.

I had written about this tragic, unsolved investigation into the murders of six women in The Hunt for the 60s’ Ripper.

My new contact, Anthony Phillips, said no one had ever contacted him about his role in the case until I responded to his message.

I called him on 2 November and he recounted a baffling incident that occurred when he was at work and which he never got to the bottom of. What he said stunned me.

A vehicle driven by the west London murderer

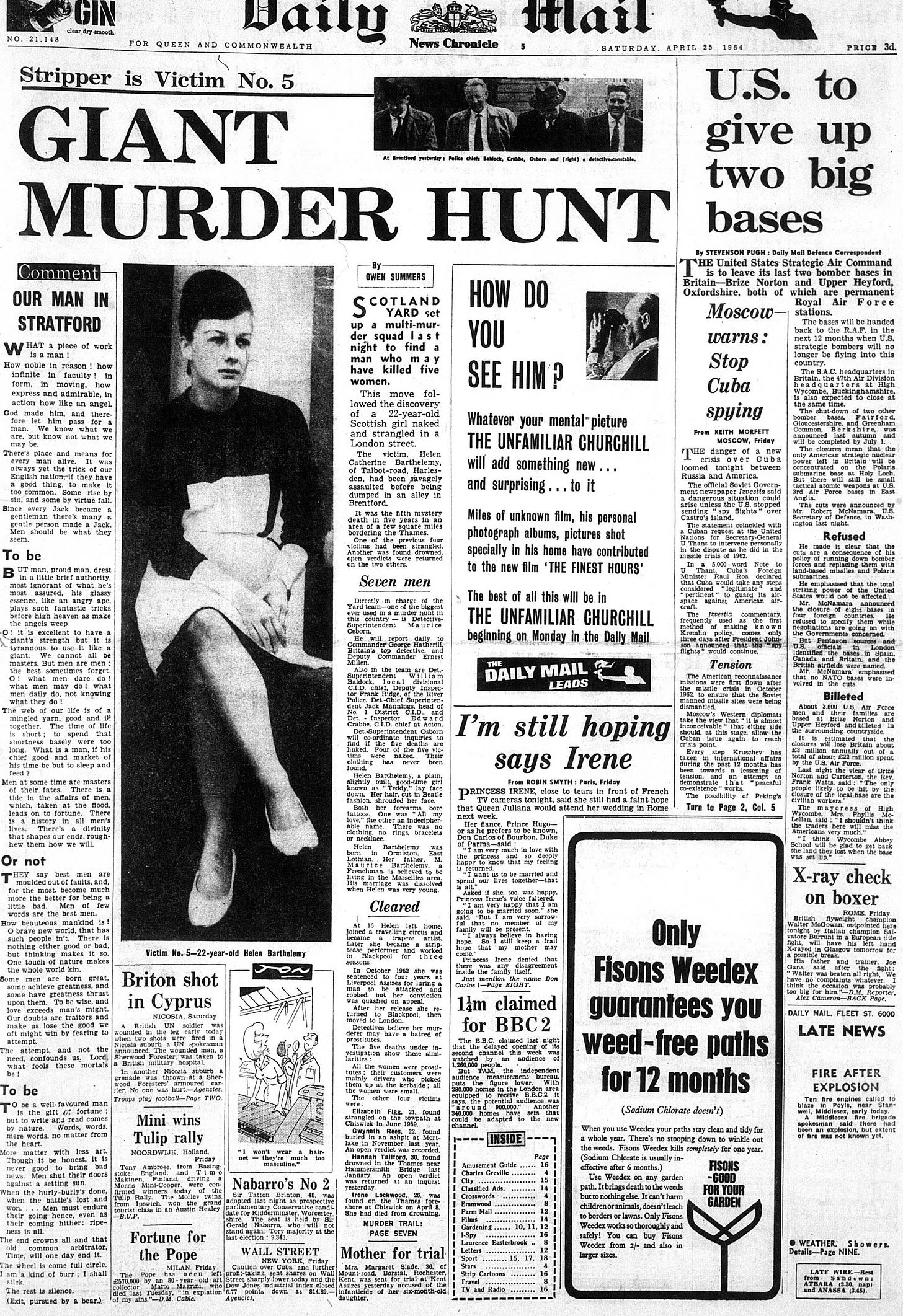

Six women were murdered in west London during 1964-5. Scotland Yard launched a huge manhunt involving hundreds of police officers, but the killings halted in January 1965. The murderer was never identified.

Mr Phillips told me he was the man whose lab skills uncovered the one solid piece of forensic evidence that detectives had. This was the micro-paint globules found on the naked bodies of four of the victims.

He also took the lead in discovering that the bodies had come into contact with the paint – transported through the air from a car-paint shop some hundred yards away – while being stored in a derelict building on the Heron Trading Estate.

Because the bodies had subsequently been left in various streets and alleys, the killer must have used a car to transport them from the trading estate. If that vehicle, probably a grey van that had been spotted, could be found with the same paint samples in it, that would have probably revealed who the killer was.

But no van or other vehicle was ever found with those paint samples.

Det Ch Supt John du Rose

When the killings stopped, the investigation was quickly run down and the victims largely forgotten by the public. There had been little empathy in the media for the women, who had been sex workers.

The Yard’s lead detective on the case, Det Ch Supt John du Rose, rather dishonestly suggested that he had known all along who the culprit had been, but that the man had committed suicide.

In reality, despite the massive resources devoted to the manhunt, the police had never really had one compelling suspect, certainly no one connected by any forensic evidence.

Which is what makes Mr Phillips’ recollection so perplexing. He told me that in 1969 he had been approached by a detective who asked him to test a sample taken from a vehicle. He did so and told the detective it was a positive match. The owner of that vehicle was the Hammersmith Nudes Killer.

And then nothing happened. The detective could not tell Mr Phillips whose vehicle the incriminating sample had been taken from. No arrest made, no announcement to the media.

Mungo Ireland in the frame

Who was the owner? Why was it apparently covered up?

Mr Phillips had wondered about it being a police officer or a prominent figure in society.

I spoke to a detective who had been part of a team that reviewed the case years afterwards. He speculated that it could have been the man mentioned all those years ago by du Rose, the one who killed himself.

This was 46-year-old Mungo Ireland, who lived with his wife in Putney and gassed himself with car fumes in his garage a couple of months after the final murder.

He was facing a court appearance for failing to stop his car, his marriage was in trouble and he was a drinker. He came under suspicion because he had been a security man on the Heron Trading Estate, where the bodies had been kept.

He left his security job in November 1964 and was working in his native Dundee as a foreman cleaner on 11 January 1965, the date the last victim, Bridie O’Hara, disappeared. The Dundee job ended a month later and Ireland returned to London.

The dead man was never a strong suspect, but, having committed suicide, he was a useful fall guy for du Rose to point to as the killer.

The People’s story

In November 1969, five months after Mr Phillips had abruptly been asked to check the anonymous vehicle sample, a story appeared in The People that Ireland had killed himself just as the police were about to arrest him.

The People’s two-page feature stated: ‘John X [as he was labelled] must have known the net was closing when he learned that detectives had made a minute inspection of the garage where he kept his car. He did not wait for them to come for him. He killed himself.’

Interestingly, the report states that after Mr X’s suicide, detectives found dust and paint particles in the back of his car that matched those on the victims.

It was also said that Mr X’s car had been spotted kerb crawling where victims had been picked up, and he bore a resemblance to a man seen at the time of the killings.

However, the whole thing was a piece of propaganda planted in The People.

The story clearly alludes to Mungo Ireland, but he was certainly not in London when O’Hara was last seen. He did not look like any suspect and he was not seen kerb crawling.

Moreover, his car and garage were never searched. Police only became interested in Ireland two months after his suicide, when his wife was interviewed. He is mentioned in the final police report on the case, but does not emerge as a suspect that ever really interested detectives.

And in that report there is no mention of incriminating paint samples found in his car.

In addition, there had been nothing stopping du Rose appearing at Bridie O’Hara’s inquest in February 1966 to state officially that he knew who the killer was a year before. Instead, his deputy, Bill Baldock, told the inquest that 120,000 people had been interviewed and more than 4,000 statements taken.

However, with no one charged, the official verdict had been ‘murder by person or persons unknown’.

Was Ireland implicated to deflect from the real murderer?

I suggest in The Hunt for the 60s’ Ripper that du Rose’s flimsy claim that he had known the killer’s identity all along was a face-facing manoeuvre from one of Scotland’s Yard’s most lauded detectives.

Du Rose had his ‘four-day Johnny’ reputation – the time it was said it took him to solve a crime – but he had failed with his biggest ever case, the Hammersmith Nudes inquiry.

So his claim, which he made explicitly to BBC television on his retirement in 1970, that he had inadvertently driven the killer to his suicide, could be seen as an unworthy attempt to take credit where it was not due.

Mr Phillips’ suggestion that police located the killer’s car in 1969 throws up another possible interpretation.

As The People’s story – which had du Rose’s fingerprints all over it – came out five months after Mr Phillips was asked to check the sample, could the bid to implicate Mungo Ireland have been disinformation?

In other words, if there was a cover-up to protect the real killer, could pushing Ireland into the frame have been an attempt to bury the truth about the driver of the car with the incriminating paint specks in it?

Of course, all of this is speculation, caused by a new and baffling piece of news. The whole case taunts us from history with unanswered questions.

I mentioned Mr Phillips’ remarks to criminologist Prof David Wilson, with whom I appeared on Dark Son: The Hunt for a Serial Killer, the BBC documentary about the case.

He found them interesting, but asked if this didn’t just cause more heat than light.

I agreed. It implies a level of conspiracy – if there was one – that will probably remain resolutely unexplained.

Unless someone finally comes forward to reveal who was driving that car.

Thanks, Emma

Brilliant book. So engrossed in it I finished it in one day! Could not put it down.