New insights into female psychopaths

As Sky announces a documentary on the Dena Thompson case, researchers have been reassessing assumptions about women with an appetite for money, manipulation and sometimes murder

Sky Documentaries has recently announced a new commission about the Dena Thompson case in the UK.

Thompson was released from prison in 2022 after serving 19 years for poisoning her second husband, Julian Webb, with anti-depressants in his curry.

She had told Webb she was suffering from cancer and persuaded him to hand her £25,000 of his savings for treatment, before poisoning him.

She was inevitably labelled the ‘Black Widow’ by the media because of her history of bigamy and conning men out of money.

Thompson used lonely hearts columns to contact men, whom she manipulated into giving up their life savings or their homes with bizarre but convincing stories.

The three-part series, which has not been scheduled yet, is said to include first-hand testimony from those affected, with exclusive access to her first husband, who ended up homeless, believing he was on the run from the mafia.

Differences between male and female psychopaths

It is easy to see why such a case is attractive to documentary makers. Women who display such elaborate criminal behaviour are rare.

Are female psychopaths more prevalent than we always assume?

The popular image of the psychopath is cold-blooded men such as Norman Bates or Hannibal Lector in fiction, while in the real world there are the chilling examples of the likes of Fred West and Peter Sutcliffe.

A recent feature in The Guardian highlighted the fact that female psychopaths are out there, but their poisonous personalities, while damaging to others, present differently, more subtly, than those found in the violent male examples.

Dr Clive Boddy, quoted in The Guardian piece, from Anglia Ruskin University, is an expert on psychopaths in the business world.

Thompson certainly showed a cold-blooded disregard and lack of empathy for those she controlled. Money, power over others and control were the objectives she pursued.

Boddy is quoted as saying: ‘A small but mounting body of evidence describes female psychopaths as prone to expressing violence verbally rather than physically, with the violence being of a relational and emotional nature, more subtle and less obvious than that expressed by male psychopaths.’

Thompson was not violent, but she was deadly, using what is often seen as a traditionally female mode of killing – poison.

Much research has been done on male psychopaths, and these findings are often used as benchmarks for assessing psychopathic traits. Which is why insights into female psychopathy are being reassessed by some academics.

Boddy believes the ratio of male to female psychopaths in society could be roughly equal, rather than the 10:1 ratio often cited in studies.

An interesting book on this subject is Snakes in Suits, by Paul Barbiak and Robert D Hare. This looks at workplace psychopaths, those narcissists who focus fiercely on money, power and control.

A useful piece of advice that emerges in that study – if you suspect someone in your workplace is that way inclined, steer well clear of them.

It seems impossible to lay the Lindbergh kidnapping case to rest.

Having written about it myself in the Daily Mirror, I was intrigued by a recent piece on the case in the New York Times.

Entitled The Lindbergh Baby Kidnapping: A Grisly Theory and a Renewed Debate, it recalls the appalling kidnapping and death of the infant son of aviator Charles Lindbergh, an event that obsessed the media on both sides of the Atlantic

Little Charles Augustus Lindbergh Junior was 20 months old when he was snatched from his family’s rural mansion near Hopewell, New Jersey, on 1 March, 1932.

Lindbergh senior had become a national hero when, in 1927, he became the first man to fly solo non-stop across the Atlantic from New York to Paris. Such national celebrity had clearly made him a target for kidnappers.

A ransom demand was made for $50,000 – around half a million pounds today. This was eventually paid, but the toddler was later found dead by a roadside.

He had been dead for a couple of months, so there was never any intention to return him after the ransom was met. One theory was that the kidnappers had dropped the child while abducting him.

Bruno Richard Hauptmann, 35, a German carpenter from the Bronx was eventually implicated for the crime. A gold certificate used to pay the ransom was traced to a garage in New York where Hauptmann had paid for petrol.

He died in the electric chair in 1936. However, the case has remained controversial since that time.

The New York Times feature picks on the lingering doubts about the case. Did Hauptmann act alone? Was he even guilty?

Most extraordinarily, it cites speculation by Lise Pearlman, a retired California judge. She argues that Lindberg himself may have had a hand in the abduction.

Her proof is circumstantial, centring on what we know about Lindberg today. A Nazi sympathiser who believed in eugenics, a racially biased and now discredited theory about how to genetically develop a superior population.

Lindberg was involved in eugenics research. Perlman’s gob-smacking theory is that he may have wanted to use his boy in the experiments. The boy had an unusually large head and took medicine for rickets, and may therefore have been considered inferior and a subject for experimentation.

Lindberg certainly had an unsavoury side to his character, but such Frankenstein assertions about him seem far-fetched.

The Times story demonstrates, however, what can happen when a police investigation is flawed, an international media circus follows it and questions linger after the trial and execution.

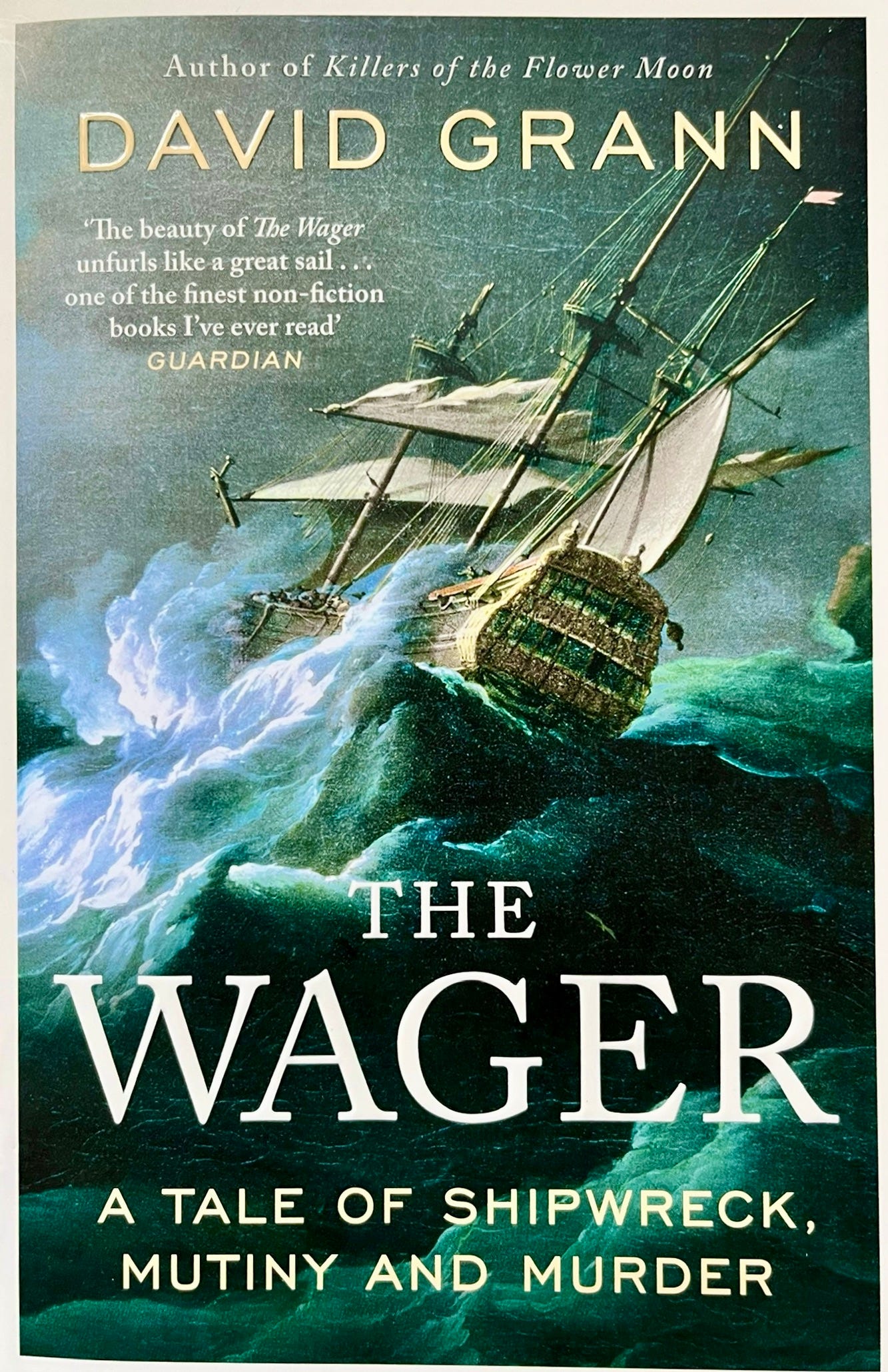

My book of the week is The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder by David Grann.

Grann, a distinguished writer for the New Yorker, also wrote the brilliant Killers of the Flower Moon. The Wager is a long way from that tale, but does again focus on historic events and wrongdoing.

It charts events in the early 1740s when a British squadron of warships set off to round Cape Horn and sabotage Spanish ships operating in the area. Horrendous storms split the British group up, with one of their number, The Wager, being washed up on an island off the coast of Brazil.

It becomes Lord of the Flies with adults, as starvation, thieving, breakdown in naval discipline, factions and murder unfolds – with suspicions of cannibalism.

Brilliantly researched and expertly told through the eyes of those involved (who kept journals and logs), it’s an engrossing read – and said to be another evolving project for Flower Moon team Martin Scorsese and Leonardo DiCaprio.