Real police scandals give Line of Duty its punch

The BBC's compelling corruption drama works on two levels – as escapist entertainment and a critique of the UK's deteriorating justice system

The stories are fiction, the corruption is real

It was a tragic killing by police that inspired Line of Duty, the BBC’s international hit series and the UK’s most watched drama this century.

Creator and writer Jed Mercurio said the incident that sparked his series was the Met’s inadvertent shooting of an innocent man and their dishonesty in its aftermath. Mercurio was referring to the 2005 shooting by officers of Jean Charles de Menezes at Stockwell tube station in London. De Menezes, a 27-year-old Brazilian electrician, had been mistaken for a suicide bomber. Afterwards, police said he had refused to obey instructions when challenged, which was later found not to be true.

This tragedy is reimagined in the opening moments of the first episode of Line of Duty. Officer Steve Arnott is a member of an armed anti-terrorist team raiding the home of a supposed jihadist bomb-maker. The problem is that the man, Karim Ali, has been misidentified. He is a normal family man but is nevertheless shot dead. Chief Inspector Philip Osborne then orders Arnott’s team to concoct false statements to suggest the man acted aggressively when asked to surrender.

This revealed Mercurio’s intention in writing a series focusing on corruption, because as he explained to The Guardian before the first episode was broadcast in 2012, “I appreciate the value of escapism, but there must also be a platform for television fiction to examine our institutions in a more forensic light.”

So, the unifying idea was set from Line of Duty’s opening sequence – this was escapist entertainment that resonated to corruption scandals and police wrongdoing in the real world. Along with the plot twists and car chases, Line of Duty’s storylines are permeated with the most shocking police scandals of recent times.

While not intended to be a police-bashing show, its aim is to explore how a couple of bad decisions can compromise people who enter public services initially with good intentions. As the series progressed, however, it became stronger in mirroring contemporary wrongdoing in Britain’s institutions.

The Real Ted Hastings

I rewatched the whole six series and replayed many scenes when writing The Real Ted Hastings, just published by Mardle Books, which explores the true corruption that powers the storylines. Again and again real-world parallels appear in the series.

Notorious investigations referenced in it have included the murders of teenage student Stephen Lawrence and private investigator Daniel Morgan. Jimmy Savile’s showbiz career built on sexual abuse has featured several times.

Other parallels include the killing of Maltese investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia with fictional character Gail Vella in Series 6. Earlier, the wrongful 16-year imprisonment of Stefan Kiszko for a 1975 murder he did not commit inspired the framing of Michael Farmer in the fourth series. There are many further true scandals loitering with intent in Line of Duty.

When it comes to a role model for Superintendent Ted Hastings, Line of Duty’s anti-corruption boss, we have to go back to the 1970s to find a Met Commissioner who epitomised his strong-minded integrity.

Robert Mark, later knighted, staked his reputation on confronting the culture of brazen corruption in Scotland Yard’s Criminal Investigation Department (CID). He is still remembered as the anti-corruption chief who shook up a complacent Scotland Yard and rooted out hundreds of crooked cops. It is no surprise he is often cited as the corruption-buster who is the closest frame of reference for Hastings.

There are differences between them. Mark was a Manchester man working in London, while Hastings is from Northern Ireland and based in an unidentified Midlands city. Their ranks are different – Mark was the Met Commissioner in charge of strategy, while Hastings is a superintendent directing investigations. Hastings is eventually suspected of being bent himself, while Mark never was.

The similarities, however, highlight a shared lineage. Both faced hostility and pariah status from fellow officers as they dug into allegations of criminality in their ranks. Mark shook up the CID when he created A10 to chase down dishonest detectives. Hastings, of course, heads its fictional counterpart, AC-12. He is accused in Season 1 of being a zealot in his fervour to investigate fellow officers. Mark was similarly accused of being more interested in arresting policemen than criminals.

Jed Mercurio’s use of high-octane drama to explore a powerful subject that increasingly hits the headlines – police wrongdoing – is in a long tradition of writers who have used real cases as inspiration for their fiction.

Edgar Allan Poe, Agatha Christie, Truman Capote…

Agatha Christie reworked the notorious kidnapping and killing of the toddler of aviator Charles Lindbergh and his wife, Anne, in 1932. A $50,000 ransom was demanded. This was handed over, but the little boy, Charlie, was found dead. He had probably died during the kidnapping two months earlier. Christie followed the case and was affected by this shocking outcome. In Murder on the Orient Express she has the victim, Mr Ratchett, revealed to be a gangster called Cassetti who had also kidnapped a child and allowed the family to believe it was alive while extorting a ransom. Cassetti is murdered in retribution.

Fiction writers often explore disturbing crimes to gain a glimmer of understanding into how they occur. In 1843, Edgar Allan Poe’s psychological mystery The Tell-Tale Heart echoed a contemporary murder, that of elderly, wealthy Joseph White in 1830 in Salem, Massachusetts. The case fascinated observers at the time as a study of guilt and ruthless indifference to the victim.

Truman Capote’s 1966 non-fiction novel In Cold Blood examined the murder of the Clutter family in Kansas seven years earlier. In her 1996 novel Alias Grace, Margaret Atwood explored the true story of Canadian girl Grace Marks, who, with another household servant, James McDermott, was tried for the murder in 1843 of her employer and his mistress.

Mass shootings, such as the one at Columbine High School in 1999, were reflected in Lionel Shriver’s novel We Need to Talk About Kevin.

A TV drama reflecting British justice in crisis

Reimagined as fiction, such shocking events can be deconstructed to posit some comprehension of the motivations and causes behind them.

Professor Heather Marquette, who has spent more than 20 years researching corruption, has said, “Watching Line of Duty is practically research… while I appreciate that not everything in the show is as it is in real life, it can help bring corruption research to life… [It] presents a vision of a police service in the UK under significant pressure. And it’s not just the police. The whole justice system is fraying at the seams in Line of Duty. From prison wardens… to the yawning, incompetent duty solicitor who sits idly by while an innocent and vulnerable young man wallows in prison, Line of Duty suggests a system that can’t effectively fulfil its purpose and risks losing public trust. This is why the work of AC-12 is so important. It’s about public trust in the law.”

Some political commentators even cite Line of Duty as a bellwether of the state of contemporary Britain, with its Party-gate, Wallpaper-gate, lobbying, sexual misconduct, PPE procurement and other scandals.

“The British state is like Line of Duty, but with no AC-12,” said journalist Paul Mason. “While nobody in their right mind thinks Line of Duty is real, its metaphoric truth is: when dealing with the commercialised and fragmented British state, you have to assume that everybody is on the make, everyone is gaming the system, everyone has something to hide, and that behind every investigation there is a cover-up.”

Mercurio acknowledged how the series evolved from its first series, a time of some optimism during the 2012 London Olympics, to the sixth series in 2021. By the time of that last series, the references to real corruption scandals were more pronounced than ever.

Interviewed on the Den of Geek site, the writer said, ‘We aired season one during the summer of the 2012 London Olympics when we were a very small, unheralded police drama buried in the BBC Two schedule. Looking back to that time, it did feel like the country was a very different place. To quote LP Hartley, it’s like a foreign country, how it felt then in terms of our national pride and the shared experience of positivity.’

Mercurio could not pinpoint the exact moment the country had lost that positivity. ‘It appears to have been a progression towards a system now where very senior politicians can visibly be corrupt – and let’s not use any other word – in a way that I think is new in this country,’ he said.

Corruption – worse than it was in the 1970s

In terms of policing, today’s crises-strewn Met is in a far deeper mess than it was in Robert Mark’s time.

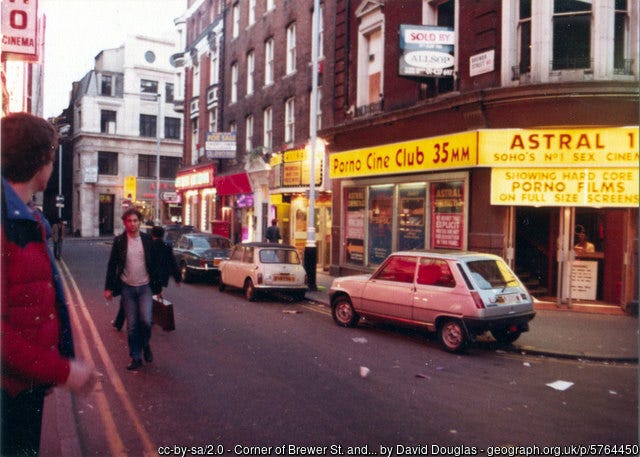

Where detectives once met villains in a smoky Soho pub to get a backhander, today’s corruption appears to be more sophisticated and entrenched. The rather terrifying secret 2002 police report based on Operation Tiberius revealed that crime networks were infiltrating the force with ease and that few rogue officers were ever prosecuted. The corruption was described as ‘endemic’. Police intelligence had been leaked, evidence ‘lost’ and officers joined in crimes such as drug importation and money laundering.

Fast forward to 2021, when Commissioner Cressida Dick said her force had the odd ‘bad ’un’ in its ranks. This could not have been more tin-earred, coming as it did on the day PC Wayne Couzens pleaded guilty to the murder and rape of Sarah Everard. The Met appeared to have regressed from Robert Mark’s confrontation with CID, whom he called ‘the most routinely corrupt organisation in London’.

It was hard to escape the conclusion that once again the Met was attempting to sweep the true scale of its problems under the carpet. Today the force is in special measures following the cascade of shocking revelations –

the heavy-handed policing of the vigil for Sarah Everard

violent misogyny and racism of officers

officers taking and sharing murder-scene photos of two sisters

the Casey Report (Met is institutionally racist, misogynistic and homophobic)

the recent report by HM Inspector of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services that the Met could again fail to spot a serial killer at work as it did in the Stephen Port case.

Multiple bad ’uns.

As Line of Duty’s millions of fans wait and hope for news of a seventh series, we may wonder if Jed Mercurio is currently scratching his head over which of the multitude of current police scandals to include next time.