An unexpected find at the Met Police Museum

I was fascinated to find that crucial evidence from an infamous wartime murder case has been carefully preserved

Research is the most enjoyable phase of writing a book for me.

Sometimes visiting an archive or interviewing a person turns out to be a disappointing endeavour. On another occasion you don’t just uncover what you hoped to find, but find something totally unexpected.

At the London Metropolitan Archives I was stunned to see a message written by the serial murderer Gordon Cummins to his wife on the morning of his hanging in 1942. I’ve included the contents of this extraordinary letter in my forthcoming book, Force of Darkness: Confronting Blackout Killer Gordon Cummins.

A short while before Christmas, it was on a visit to the Metropolitan Police Museum in Sidcup, south London, that I was stunned to make another discovery in regard to the same case.

Vital fingerprint evidence

This was a speculative outing for me – I was simply curious to see what artefacts and archives this police museum held (the website is not that detailed).

The museum consists of one large room inside the police station. You have to make an appointment to visit and join a guided 90-minute tour of the exhibits. Among the visitors are detectives also curious to learn about past investigations and forensic breakthroughs.

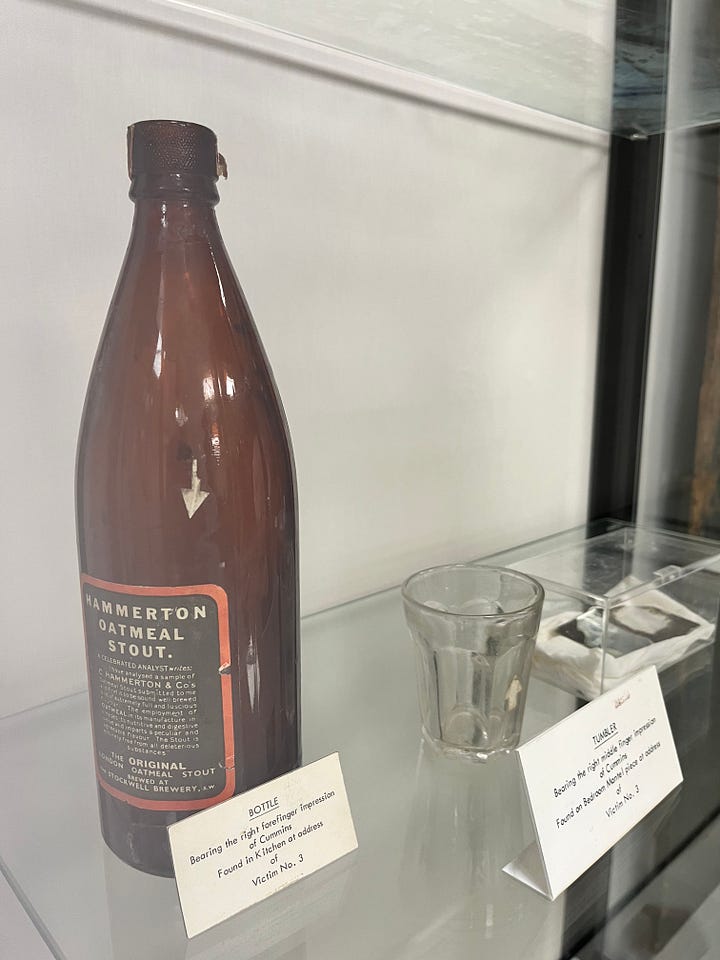

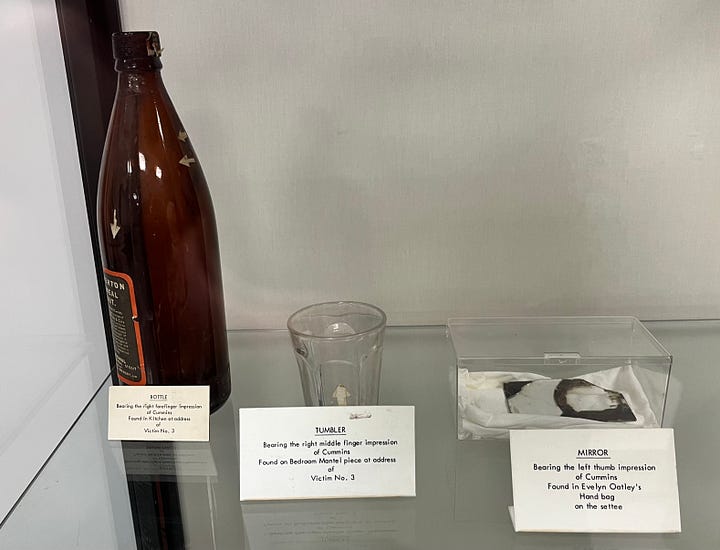

Having spent the best part of a couple of years researching the Gordon Cummins, I was fascinated to see that the Metropolitan Police Museum had on display the items marked by his fingerprints that did so much to establish his guilt at the Old Bailey.

Cummins, a 28-year-old RAF cadet, had been charged with attacking two women and murdering four others in one week during 1942. However, he actually stood trial for the murder of only one of his victims, Evelyn Oatley.

She was a married woman living apart from her husband. She was known to solicit around Piccadilly and this was how she encountered Cummins.

His attack on her was vicious, but he had recklessly left forensic clues behind, namely his fingerprints. The veteran Scotland Yard fingerprint expert Fred Cherrill found these marks – on a tin opener and broken mirror – and these offered clear proof that Cummins, despite his constant denials, had been in her flat.

Cherrill was challenged fiercely and at length by the defence team, but the expert stood up to this and the jury accepted his assurance that the prints were Cummins’.

The RAF man decided to go into the witness box and give evidence in his own defence, but he was an appalling liar and was quickly forced to admit he had lied to police.

It is sobering to realise that these everyday household items, so easily discarded by Cummins, could in the end expose him as a depraved killer.

He appealed but this dismissed. Cummins was booked to meet on 25 June 1942 the hangman Albert Pierrepoint at Wandsworth Prison (as recounted in my previous post).