Sixty years on – will the identity of London's Hammersmith serial killer remain a secret forever?

The body of Bridie O'Hara was found in 1965, but Scotland Yard's investigation never got close to trapping the man who killed her and five other women

On 16 February 1965, odd-job man Leonard Beauchamp, aged 26, was at work at the Surgical Equipment Suppliers on the Heron Trading Estate in west London.

He needed some liquid soap for the dispenser in the men’s toilet and went outside to a shed to fetch it. His firm’s building was alongside a railway embankment, and he often checked down the side of it for discarded cast-off property that he sometimes found a use for.

On this day he found something out of the ordinary. ‘I first noticed a pair of feet and I could see them up to the ankles,’ he later told detectives. ‘My first reaction was that I was looking at a dummy.’

Nobody would take his claim that there was a body outside seriously until the production manager told everyone not to touch anything. Acton police were called.

Bridget ‘Bridie’ O’Hara, 27, had last been seen on a night out in Shepherd’s Bush over a month previously. Bridie was a sex worker, the last of six murdered by a kerb-crawling serial killer on the streets of west London between 1964 and early 1965.

The victims were Hannah Tailford, Irene Lockwood, Helen Barthelemy, Mary Fleming, Frances Brown and Bridie O’Hara.

All were sex workers whose clients were often kerb-crawlers. They were petite, around 5’1”. The killer’s preferred MO was asphyxiation, after which he would remove all the victims’ clothing and belongings that he could, even dentures, presumably to avoid leaving forensic clues behind.

Hundreds of police hunt the serial killer

The killing spree prompted a huge response from Scotland Yard. Hundreds of uniformed and detective officers were drawn into the manhunt that dragged on for months.

Chief Superintendent John du Rose was called in to take charge after Bridie O’Hara was discovered. At his command were some 200 CID officers and another 100 men and women in uniform.

Du Rose also requested a further 300 officers from the newly formed Special Patrol Group. He got them.

Police observation points were set up around a 24-square-mile area of west London to monitor drivers going into the Hammersmith/Shepherd’s Bush area. Drivers spotted doing so three times were visited by detectives.

Officers were instructed to spend time in pubs, cafes and clubs from Soho to Shepherd’s Bush. Here the job was to mingle with prostitutes and punters, sifting for leads on suspicious characters.

Women police constables dressed as sex workers and loitered on the streets around Queensway, Kensington High Street and Shepherd’s Bush, recording on hidden tape machines conversations they had with cruising men.

Around 300,000 vehicles were logged by the police observation posts, 1,700 drivers spoken to, including kerb-crawling doctors, clergymen, company directors and lawyers.

Thousands of people were interviewed, statements taken. Officers bought new cars with the overtime earned.

And yet despite the monumental amount of legwork and records generated, du Rose and his team never really had one good suspect to pursue linked by forensics or witnesses.

Little sympathy for the victims

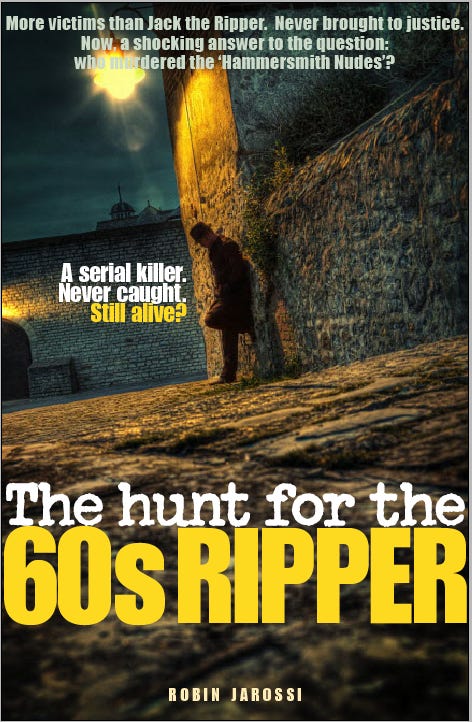

I spent many months researching this case for my 2017 book The Hunt for the 60s Ripper.

Reading newspaper coverage of the case at the British Library for many hours, what struck me was that for all the volume of effort that went into the investigation, there was hardly any sympathy in the press for the victims.

This was reflected by the speed with which du Rose and the Scotland Yard hierarchy wound down the investigation once the murders stopped.

It was true that the probe had put a strain on Metropolitan Police resources. But du Rose rather dishonestly claimed that he had known who the culprit was all along, but that this man – a drunk who was never really a compelling suspect at all – had committed suicide and could not be brought to justice.

Du Rose’s dishonest claim was not only an attempt to shut down speculation about the spectacular failure of his investigation and restore the gloss to his reputation as a top detective, but it was also a cruel disservice to the families of the victims.

Will the killer ever be unmasked?

I’ve written elsewhere on Substack about why the huge manhunt came to nothing.

However, as we pass the 60th anniversary of Bridie O’Hara being found, speculation continues about the identity of the man who cruelly ended so many lives. If he was in his twenties at the time, he could still be alive today.

My own feeling is that because du Rose and his colleagues were so quick to wash their hands of the case and there was so little public/media pressure to find this killer of these disreputable women, we will never know now. When the headlines ceased so did public interest in the case.

There is little likelihood that any new evidence will emerge, though I did report on one intriguing development in the case last year.

The BBC TV documentary sparked by my book, and which I appeared on, Dark Son: Hunt for a Serial Killer, suggested strongly that convicted killer and rapist Harold Jones was the culprit.

I point out in The Hunt for the 60s Ripper that Jones, who died in 1971 from cancer, had lived within a couple of streets of Bridie O’Hara and Frances Brown in Hammersmith, and that this was a hotspot identified by a leading geographic profiler I consulted, Kim Rossmo, as being one the police should have focused on.

Jones certainly had psychopathic tendencies, having served 20 years for attacking and killing two girls when he was a 15 year old growing up in Abertillery, Wales.

It was clearly a huge missed opportunity that detectives did not spot Jones at the time. He had been using aliases while living in London – Harry Stevens, Harry Jones – and was certainly a conniving, calculating man.

But had the investigation been more focused, as a modern one would, and not sidetracked by what one detective described to me as a ‘huge wall of administrative shite’, they may have been able to spend more time checking out the past lives of people such as Harold Jones.

Jones should have been a prime suspect and was a stronger suspect than anyone else looked at by detectives. He worked on the Heron Trading Estate where O’Hara was found and where some of the bodies had been kept.

There was strong witness evidence that the killer deposited the victims while driving a grey Hillman Husky-type van. Did Jones drive? Did he own such a van?

These are questions a researcher like myself cannot answer because we don’t have access to the driving records of the time. However, they would have been simple questions for detectives at the time to resolve.

From what I have seen, there is no indication that police even spoke to Jones at all.

But if Jones had access to such a van, he would have been heading to custody at Shepherd’s Bush nick at the speed of James Bond’s Aston Martin.

It is now some seven years since I wrote The Hunt for the 60s Ripper, but the secret of who was behind these appalling crimes keeps the questions and interest alive.

I will be recording an interview with a podcast show in Ireland next week. Of which, more later…

• Mail online feature on the 60th anniversary of the ca

Robin, my book 'Exposing Jack: The Hammersmith Nude Murders' is currently being published by Pen & Sword Books for release later this year. Regards Chris Clark.